Comes the news that the British online food retailer Ocado is making major investments in two vertical farming companies.

this week in a bid to become what it described as “a leader in the newly emerging vertical farming industry”. First, the company’s ventures arm has signed a three-way joint venture deal with 80 Acres Farms and Priva Holding. 80 Acres and Priva have been working together for over four years to design turnkey solutions to sell to vertical farming clients worldwide, with forecast revenues in 2019 of over $10m. The new venture will be called Infinite Acres. ... “We believe that our investments today in vertical farming will allow us to address fundamental consumer concerns on freshness and sustainability and build on new technologies that will revolutionise the way customers access fresh produce,” Ocado CEO Steiner explained.Will this technology revolutionize the way customers access fresh produce? Is this a big deal for sustainability? A few years back in an essay titled: “Why I’m empowering 1,000’s of millennials to become #realfood entrepreneurs through Vertical Farming”, Elon Musk’s younger brother Kimball announced that he was going to invest in urban farm incubators in multiple cities. While there is certainly room for vertical farms in urban food systems to supply hydroponic greens and herbs to upscale grocers and restaurants, Musk’s ambitions go far beyond that.

The Kitchen’s mission is to strengthen communities by bringing local, real food to everyone. With our commitment to local food sourcing, our restaurants have become major catalysts for local food economies — across Colorado, Chicago, and now Memphis — serving real food to over 1 million guests a year. Meanwhile, our non-profit The Kitchen Community has built 300 Learning Gardens across the country — inspiring 150,000 kids each day as we get them outdoors and teach them about real food.The real and imagined impacts and potential of vertical farms had very much been on my mind. Just the week before, a friend on Facebook shared a story on the amazing ecological efficiencies of a new vertical farm and asked, “Is this stuff real or is it just hype?”

But the impact of those initiatives are a drop in the ocean compared to what’s needed. By 2050, 9 billion people will live on our planet, and 70% of them will live in cities. These people need food. And the data is clear: they will want local, real food.

The industrial food system will not solve this problem (more Deep Fried Twinkies, anyone?). Instead, finding the right solution presents an extraordinary opportunity for new entrepreneurs. As I’ve said before, “Food is the new internet.” I know the next generation is excited to join the #realfood revolution, and shape the future.

That’s why I’m thrilled to introduce a new company in The Kitchen’s family: Square Roots.

Introducing Square Roots

Square Roots is an urban farming accelerator — empowering 1,000’s of millennials to join the real food revolution. Our goal is to enable a whole new generation of real food entrepreneurs, ready to build thriving, responsible businesses. The opportunities in front of them will be endless.

Square Roots creates campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, hydroponic vertical farms, right in the hearts of our biggest cities. On these campuses, we train young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, real food all year round and sell locally. And we coach them to create forward-thinking companies that — like The Kitchen — strengthen communities by bringing local, real food to everyone.

The article asked, “Considering it uses 95% less water than regular farms, could vertical farming be the future of agriculture?” and told the story of a vertical farm in Newark, NJ in an old laser tag facility.

At AeroFarms in Newark, New Jersey, crops are stacked more than 30 feet high in a 30,000 square foot space that was formerly a laser tag arena. They use aeroponic technology, which involves misting the roots of the plants, using an astonishing 95% less water than more conventional farming methods. David Rosenberg, CEO of AeroFarms told Seeker, “Typically, in indoor growing, the roots sit in water, and one tries to oxygenate the water. Our key inventor realized that if we mist nutrition to the root structure, then the roots have a better oxygenation.”

AeroFarms doesn’t use any pesticides or herbicides either. The plants are grown in a reusable cloth made from recycled plastic, so no soil is needed to grow them. They also use a system of specialized LED lighting instead of natural sunlight, reducing their energy footprint even further. “A lot of people say ‘Sunless? Wait. Plants need sun.’ In fact the plants don’t need yellow spectrum. So we’re able to reduce our energy footprint by doing things like reducing certain types of spectrum,” Rosenberg said.

IT’S ALWAYS SALAD GREENS

I would say that it’s mostly hype, certainly not revolutionary. These projects always center on salad greens and herbs, crops that sell at a premium and deliver very few calories, but a lot of water.Crops require light, water, and a growing medium – three things in abundance at low prices on rural farms in the form of sun, rain, and soil. The economics of paying for light and rain, plus the economics of real estate are such that these projects cannot pencil out for any crops other than high end greens and vegetables. There is a reason why so much of the innovation in hydroponic growing systems came out of marijuana production. The ROI per square foot is far greater than for oats.

The future of urban farming is in crickets and other insects, mushrooms and other fungi, algae and yeasts, and in vitro meat. If you want to go beyond premium salad greens and herbs, you need to focus crops or herds that don’t require lots of space, water or sunlight. More importantly, if you really want to lower the impact of food production, urban farming needs be able to close nutrient cycles in dramatic ways.

[ For a more enthusiastic and rigorous take on the potential of vertical farms see this piece by Dan Blaustein-Rejto of the Breakthrough Institute.]

The exception might be in cities like Detroit, where a collapsing urban footprint changes the economics of the real estate. As a city economy grows, agglomeration increases the productivity per square foot, driving up rents which leads to the necessity of greater productivity per square foot. If urban farming catches on, it requires more square feet, driving up rents, requiring greater productivity per square foot, driving up the required productivity per square foot driving up the price required to be charged per square foot of product. TLDR: this model cannot work for barley, oats, canola, cowpeas, black beans, soybeans, pinto beans or any other serious sources of calories or protein in an urban setting. The revolution is not going to be powered by expensive salad greens.

Tamar Haspel helpfully chimed into that discussion to share an article she did for the Washington Post on the ledger of environmental challenges and benefit of vertical farming. In terms of growing lettuce greens she tallied the use of less land, less water, less fertilizer and less pesticides as four environmental benefits of vertical farming. On the down side, she pointed out that one of the biggest trade off was foregoing solar power for electricity.

However, unless the vertical farm is powered by nuclear or renewables or both there is one big sticking point: But before you shell out for the microgreens, there are a couple of disadvantages. The first is that you’ll have to shell out a lot, and the second gets at the heart of the inevitable trade-off between planet and people: the carbon footprint. If you farm the old-fashioned way, you take advantage of a reliable, eternal, gloriously free source of energy: the sun. Take your plants inside, and you have to provide that energy yourself. In the world of agriculture, there are opinions about every kind of system for growing every kind of crop, so it’s refreshing that the pivotal issue of vertical farming — energy use — boils down to something more reliable: math.

There’s no getting around the fact that plants need a certain minimum amount of light. In vertical farms, that light generally is provided efficiently, but, even so, replacing the sun is an energy-intensive business. Louis Albright, director of Cornell University’s Controlled Environment Agriculture program, has run the numbers: Each kilogram of indoor lettuce has a climate cost of four kilograms of carbon dioxide. And that’s just for the lighting. Indoor farms often need humidity control, ventilation, heating, cooling or all of the above.

… Let’s compare that with field-grown lettuce. Climate cost varies according to conditions, but the estimates I found indicate that indoor lettuce production has a carbon footprint some 7 to 20 times greater than that of outdoor lettuce production. Indoor lettuce is a carbon Sasquatch.

She goes on to explain that with more efficient lighting systems and access to nuclear and renewable energy sources, vertically grown lettuce can close a big part of that gap, but it’s still a steep climb.

Before moving on to the reasons why I’m enthusiastic about farming crickets and other insects, mushrooms and other fungi, algae and yeasts in urban settings, I want to circle back to the economics of real estate that serves as the stake through the heart of mass scale vertical farming of traditional crops.

A LITTLE PERSPECTIVE ON SCALE

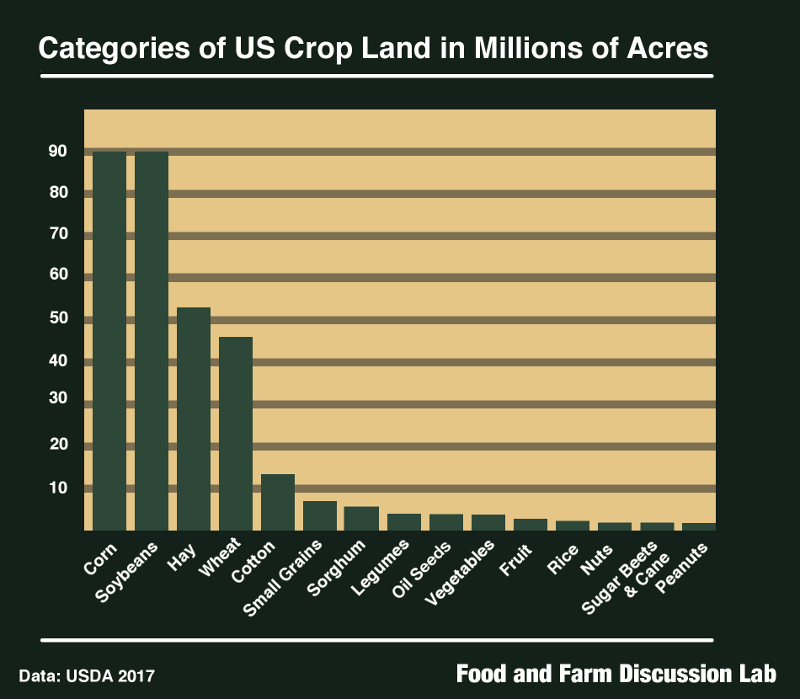

First let’s put some things in perspective about scale. One of the larger well known urban rooftop farm in New York City is 42,000 square feet. 42,000 square feet sounds like a lot of square feet. But retail and office space are measured in square feet. Farms are measured in acres and 42,000 square feet is pretty much one acre. 0.964187 acres to be exact. New York state has 7 Million acres of farmland across 36,000 farms. That’s just the state of New York, which isn’t a particularly rural state. Urban real estate is denominated in square feet. Farms are denominated in acres.Field corn (not grown for ethanol) accounts for over 50 million acres of farmland. Wheat, another 50 million acres. That’s 100 million acres just in two major grains. But let's put that aside. Nobody thinks were are going to grow corn and wheat in urban vertical farms, I just think it’s important to start with a baseline of the scale of the footprint of where most of our calories come from. And if you think we should be getting less of our calories from corn and wheat – and I’d agree with you – just keep in mind that no other crops come close on calories per acre, so any shift away from corn and wheat is going to drive that 100 million number upwards. Leaf lettuce is grown on just shy of 70,000 acres in the U.S. The acreage for herbs is so small it doesn't register in USDA reports and surveys outside of mint for mint oil (think spearmint chewing gum and peppermint ice cream). Total cropland in the U.S. is about 250 million acres. Nearly all domestic leaf lettuce is grown in either California or Arizona. Redistributing the production to regions with lower pressure on water supply and delivering fresher products to consumers can have some benefits, but it's hardly going to revolutionize vegetable production, much less the food system.

Let’s look at the crops that make up the core calories of a healthy diet. Barley accounts for 3.2 million acres. Lentils, dried beans and peas 2.7 million acres. Rice – 2.6 million acres. Vegetables – 4.1 million acres and half of that is potatoes, sweet corn and tomatoes. Orchards and berries – 5.4 million. 18 million acres total or 756 Billion square feet.

Let’s grant these vertical farms the wildly ambitious ability to increase yield by a third and say that shifting 10% of production into vertical farms would be a substantial impact. That would require 50 Billion square feet of urban real estate.

ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION

Now let’s back up to the point we made about real estate prices and productivity. As cities grow bigger and denser productivity rises. Similar firms cluster and generate a base of workers who circulate among them increasing knowledge and competence. Travel times are lower, so a delivery van can make more stops per hour in a city than in a suburb or rural community. With more customers in their base, firms can grow larger and take advantages of economies of scale. This is what is called agglomeration in economics. Agglomeration makes for productive, vibrant cities, but it also drives up rents. Which further puts pressure on firms to increase the productivity out of each square foot of real estate that they own or lease. To increase productivity per square foot firms can either produce more units or charge more per unit. This is why expensive herbs and greens are the only products that currently make sense in vertical farms.Now imagine what it would mean to add demand for another 50 billion square feet of real estate to US cities. Scaling up the operations of vertical farms would COMPOUND the pressure to produce crops that they can sell at high prices. While proponents often claim that as more vertical farms come online, prices will come down, for most crops the economics of cities tell us that the opposite is true.

So the economics of urban real estate are stacked against vertical farms except in places like Detroit where the urban footprint in shrinking and there is massive slack in the real estate market. But the economics for vertical farms are even steeper when we take comparative advantage into account.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Comparative advantage is an economic concept that most people have heard of but very few understand and a vanishingly small number of people “get” on an intuitive level. That’s because it is one of the most counter-intuitive concepts in economics and I balk at the headache of even attempting to put it across when I think I’ve probably already made my case as to why I don’t expect vertical farms to catch on beyond expensive herbs and greens (and maybe some heirloom tomatoes and peppers). But it’s an important concept to understand in general and for the case I’d like to make for why I think the future of urban agriculture is in mushroom and cricket farming, black soldier flies, algae and yeasts, and in vitro meat production.The economist Paul Krugman once called comparative advantage “Ricardo’s Difficult Idea” in an essay in which he explains why a concept formalized in 1817 by the philospher and political economist David Ricardo remains so poorly understood, if not outright resisted, even by economic sophisticates.

The idea of comparative advantage — with its implication that trade between two nations normally raises the real incomes of both — is, like evolution via natural selection, a concept that seems simple and compelling to those who understand it. Yet anyone who becomes involved in discussions of international trade beyond the narrow circle of academic economists quickly realizes that it must be, in some sense, a very difficult concept indeed. I am not talking here about the problem of communicating the case for free trade to crudely anti-intellectual opponents, people who simply dislike the idea of ideas. The persistence of that sort of opposition, like the persistence of creationism, is a different sort of question, and requires a different sort of discussion. What I am concerned with here are the views of intellectuals, people who do value ideas, but somehow find this particular idea impossible to grasp.

My objective in this essay is to try to explain why intellectuals who are interested in economic issues so consistently balk at the concept of comparative advantage. Why do journalists who have a reputation as deep thinkers about world affairs begin squirming in their seats if you try to explain how trade can lead to mutually beneficial specialization? Why is it virtually impossible to get a discussion of comparative advantage, not only onto newspaper op-ed pages, but even into magazines that cheerfully publish long discussions of the work of Jacques Derrida? Why do policy wonks who will happily watch hundreds of hours of talking heads droning on about the global economy refuse to sit still for the ten minutes or so it takes to explain Ricardo? Against that backdrop let me apply my meager talents to see if I can pound this into your thick skulls with any greater efficacy. Here goes.

Ricardo provided a simple two country model to show the math at work here. Consider two countries, England and Portugal, producing two identical products but at different rates of productivity.

In the absence of trade, England requires 220 hours of work to both produce and consume one unit each of cloth and wine while Portugal requires 170 hours of work to produce and consume the same quantities. England is more efficient at producing cloth than wine, and Portugal is more efficient at producing wine than cloth. So, if each country specializes in the good for which it has a comparative advantage, then the global production of both goods increases, for England can spend 220 labor hours to produce 2.2 units of cloth while Portugal can spend 170 hours to produce 2.125 units of wine. Moreover, if both countries specialize in the above manner and England trades a unit of its cloth for 5/6ths to 9/8ths units of Portugal’s wine, then both countries can consume at least a unit each of cloth and wine, with 0 to 0.2 units of cloth and 0 to 0.125 units of wine remaining in each respective country to be consumed or exported. Consequently, both England and Portugal can consume more wine and cloth under free trade than in autarky.

WIKIPEDIA: In this illustration, England could commit 100 hours of labor to produce one unit of cloth, or produce 5/6ths units of wine. Meanwhile, in comparison, Portugal could commit 90 hours of labor to produce one unit of cloth, or produce 9/8ths units of wine. So, Portugal possesses an absolute advantage in producing cloth due to fewer labor hours, and England has a comparative advantage due to lower opportunity cost.

To share an embarrassing story from my past, at the last union I worked for I had a boss who was a supremely talented union organizer and I was going through a personal rough patch and not firing on all cylinders, though I was still OK at my job. But he was constantly frustrated with me and just wanted to push me aside and do my job for me because he could do my job better than I could. And he could – he was just much more talented at union organizing than I was, especially during that sad chapter of my life. But he didn’t, because not only was he much better at my job than I was, he was much, much better at HIS JOB than I was. So it made more sense of him to concentrate on doing his job – supervising me and another ten organizers than to split his time doing his job and my job (and assigning me the minor parts of his job that he wouldn’t have time to do).

In the neighborhood I grew up in, software engineers frequently paid thirteen-year-old kids to mow a lawn in an hour that they could mow in 45 minutes. But if they were going to put in one more hour of effort that week, it was better spent working as a highly paid software engineer, not out-competing thirteen-year-old’s who mowed grass to buy grass.

So think of a simple economy composed of the city of Los Angeles and California’s Central Valley where both produce movies and tomatoes. Even if Los Angeles could produce tomatoes somewhat more efficiently than the Central Valley, the theory of comparative advantage tells us that they should still stick with movies and let Central Valley deal with tomatoes – they will both be better off. Likewise, if we imagine an economy of New York City and Iowa, where they both produce business services and corn, even if NYC can do corn better than Iowa, they should stick with business services, where they are heavyweight champion.

These are simple models and there are all sorts of situations and examples where comparative advantage doesn’t work in a clean, frictionless, straightforward way. But any narrative which attempts to make the case that vertical farms are the next big thing in agriculture needs to deal with comparative advantage rather than sidestep, ignore or dismiss the issue.

To beat this horse a bit closer to death, here is Krugman on trying to make a charitable interpretation of those who seem to be in denial about the power of comparative advantage:

Surely, we have argued, the problem is one of different dialects or jargon, not sheer lack of comprehension. What these critics must be trying to do is draw attention to the ways in which comparative advantage may fail to work out in practice. After all, economists are familiar with a number of reasons why the gains from free trade may not work out quite as easily as in the simplest Ricardian model. External economies may mean underinvestment in import-competing sectors; imperfect competition may lead to a strategic competition over industry rents; because of distortions in domestic labor markets, imports may reduce wages or cause unemployment; and so on. And even if national income rises as a result of trade, the distribution of income within a country may shift in a way that hurts large groups. In short, there are a number of sophisticated extensions to and qualifications of the model introduced in the first few chapters of the undergraduate textbook – typically covered later in the book.

Which is to say that, standard economics is not ignorant of all the reasons you may come up with for trying to dismiss the implications of comparative advantages just because you can’t shake the idea that vertical farms are a neat idea and wouldn’t it be cool if cities were self-sufficient in food production.

We’ll look at some examples of where cities would have comparative advantage going forward in terms of local food production. I think these are areas where Kimball Musk’s 1000’s of millennials will ultimately find greater success. But first, we need to look at the one big advantage an urban setting brings to agricultural production.

THE NUTRIENT CYCLE

When you grow a crop, the plant takes nutrients, most notably the old NPK – nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium out of the soil to feed and construct itself. When the crop is harvested a lot of those nutrients go with them and they need to be replaced in the soil. This creates a problem that is solved by planting nitrogen-fixing legumes and adding fertilizers, either synthetic fertilizers or manures. But they have to come from somewhere – and that somewhere is generally somewhere not on the farm.Meanwhile, the nutrients have been shipped in our simple model economies from the Central Valley to Los Angeles and from Iowa to New York City. The people eat the nutrients and then deposit the nutrients into the trash, compost bins or their toilet. This creates a waste management problem.

Nitrogen management is a huge issue in agriculture, but the nutrient cycle problem that most keeps the deep thinkers up at night is phosphorus. It’s pretty easy and getting easier to pull nitrogen out of the air to fertilize crops. We have an effectively infinite supply of potassium. However, we are running out of phosphorus that we can mine. Eventually, and the sooner the better, we need to figure out how to close the nutrient loop that mostly ends when food reaches our cities.

The modes of food production that close that loop will be the ones that make the greatest impact, both ecologically and economically. That’s why I think the future of urban agriculture will be in crickets and other insects, mushrooms and other fungi, algae and yeasts, and in vitro meat.

CRICKETS: Crickets grow to maturity in 3-4 weeks, so they do not take a lot of space to produce prodigious amounts of protein. Protein per acre is a threshold measure in food security. Protein is ecologically expensive – carbs need carbon which is easily pulled from the air and converted into structure by photosynthesis – the nitrogen in the air is bound by very tight chemical bonds which require a lot of energy to break and put it to use. Lots of protein per square foot means cricket can pay urban rents in cities where heating costs are low (crickets like the temperature to stay above 25C).

And the reason urban rents make sense is that cricket thrive on food waste. Current cricket production is geared to a higher end consumer product, which also makes paying the rent easier, but that requires a more uniform diet to achieve a more uniform tasting cricket. The big breakthrough from an environmental perspective and the ability to achieve impactful scale will be when cricket producers start selling affordable cricket feed to livestock and aquaculture producers. That will allow cricket farms to be less fussy about what they feed the crickets and will create an economical way of cycling nutrients back to rural communities from cities that can complement the current practice of composting food waste and shipping the humus to farms from cities.

BLACK SOLDIER FLIES: Even better at turning waste into usable protein is the black soldier fly larvae. The larvae can feed on human solid waste and drastically reduce the volume and weight, allowing it to be shipped as a fertile soil amendment while transforming the nutrients into protein which is ideal for livestock feed. Black soldier flies can also feeding food waste and reduce it to a soil amendment much faster than composting without producing the greenhouse gases that make composting environmentally problematic.

One startup is taking the fruit and vegetable pulp waste from a local juicery and the day-old bread from a bakery using the grubs to transform it into high-quality animal feed. Cities are full of these waste streams in dense supply chains. This kind of waste is currently mostly going to landfills where it creates greenhouse gases emissions.

MUSHROOMS: Mushrooms are a vegetable crop that has one massive advantage over lettuces and hydroponic tomatoes and peppers in an indoor growing environment. Mushrooms don’t use photosynthesis and thus don’t require light to grow. This removes a major energy input in comparison. Another thing mushrooms have going for them is that they thrive in coffee grounds and our cities are producing massive amounts of spent coffee grounds that would be relatively easy to cordon off into new supply chains. After mushrooms are harvested, the mix of spent coffee grounds and mushroom roots makes a great soil amendment that can be marketed to suburban gardeners and peri-urban farms.

algae AND YEASTS: algae and yeasts are currently being used to produce previously expensive compounds and ingredients. Sometimes developed by traditional breeding, sometimes via the techniques of synthetic biology, algae and yeast have been used to produce replacements for palm oil which is environmentally disastrous by and large and for compounds like vanillin which we generally get from vanilla farms in environmentally fragile ecosystems. algae and yeasts are also used to produce pharmaceutical compounds. Currently, sugars are used as the input for their growth and as the substrate they convert to more useful and valuable compounds, but current research and development is fairly quickly moving to make using a wider range of cellulosic biomass as a substrate more and more viable. Be one the look out for vegan milk, cheese and butter from this sector.

IN VITRO MEAT: “Test tube meat” or cultured meat is still a ways out in it developing an economically viable product, but it’s certainly coming. I expect it to be used in sausage production before we get to a satisfying vat grown ribeye, but cultured meat meat production fits our criteria for successful urban agriculture. You can produce a lot of valuable product in a relatively small space, without the need for light as an energy source and you can use urban waste streams as a valuable input.

Now, I’m not saying that there aren’t going to be vertical farms that are successful in producing and selling high-end lettuces, herbs, peppers, and tomatoes. There will be. It will be a limited, upscale market, but that niche will work. What I am saying is that those kinds of vertical farms will not ever achieve the kind of scale necessary to transform the food system in consequential ways. Nor do they do much to tackle the biggest challenges in the food system, which have to do with waste management and the nutrient cycle.

The kinds of urban ag that will transform the food system and significantly reduce the environmental impacts of food production will be those that are not fighting against the economics of cities but are leveraging the economics of cities. That means leveraging comparative advantage rather than trying to dismiss it. Most of all, it means leveraging the dense supply chains and waste streams of valuable inputs that already exist in cities, rather than trying to replace the rain, sun, space, and soil that already exist on rural farms.

The Agromodernist Moment is a project of Food and Farm Discussion Lab. If you'd like to support this column and the other work we do, consider a monthly donation via Patreon or a one-time donation via Paypal.

Comments